Before Language, Was There Trauma?

Why Talk Therapy Can’t Be the Whole Story

I. Introduction: The Problem with Narrative-First Models

A client sits in therapy, retelling their childhood abuse story. Their heart rate spikes, breathing becomes shallow, and they dissociate mid-sentence. The therapist asks them to “stay with the feeling” and explore what story they’re telling themselves. But the client’s nervous system is already overwhelmed—language is no longer a bridge to healing, but a reactivation of the pain.

This scenario reveals a core limitation of narrative-first trauma models. From psychodynamic insight to cognitive reframing, many frameworks assume that healing primarily involves talking—making sense of what happened, telling a better story, or assigning new meaning. But what if trauma occurred before the brain was capable of language? What if the nervous system was shaped by experience before the mind could process it in words?

II. The Narrative Trap: When Trauma Becomes a Story Problem

A popular quote from Gabor Maté says: “Trauma is not what happens to you, it’s what happens inside you as a result of what happened.” While this wisely redirects attention to internal experience, it can imply that trauma is fundamentally about interpretation. That healing lies in reframing the past—telling a new story, integrating the memory differently, or changing your belief about what happened.

But the nervous system doesn’t operate through narrative. It responds through physiological states: hyperarousal, freeze, collapse, dissociation. These aren’t cognitive distortions. They’re automatic biological responses.

Narrative work assumes access to the systems involved in reasoning, reflection, and symbolic meaning. But trauma often shuts those systems down. When someone is dysregulated, they’re not in a position to “tell a better story”—they’re trying to survive the present moment with a nervous system that’s reacting as if the danger is still real.

III. Trauma Before Thought: The Infant Nervous System

If trauma is something we “tell ourselves about what happened,” how do we explain infant trauma?

Infants are highly vulnerable to traumatic stress, even without language, memory, or explicit beliefs. Early relational disruptions—such as chronic neglect, misattunement, or chaotic caregiving—alter core systems of stress regulation and emotional processing.

Because emotion emerges before language.

This is true developmentally in infants, and moment-to-moment in adults.

The brain detects and reacts to threat long before we can describe it.

You feel unsafe before you think unsafe. You panic before you can narrate why. You flinch before you can explain the noise.

Neuroscience confirms this: emotional responses—like fear, shame, or rage—are initiated within 200–300 milliseconds by subcortical systems, well before the neocortex can generate conscious thought or language.

(LeDoux, 1996; Panksepp, 1998; Barrett, 2017)

In infants, this sequence is even more stark. Research in developmental neuroscience has shown that:

The HPA axis (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal) can become chronically dysregulated by early relational stress, leading to overactive or blunted stress responses.

(Gunnar & Quevedo, 2007)Amygdala sensitivity can increase, heightening threat detection even in safe contexts.

(Tottenham & Sheridan, 2009)Prefrontal cortex development—which governs self-regulation—can be impaired by early trauma.

(Teicher et al., 2016)Attachment system disruptions impair a child’s capacity to co-regulate with caregivers, leading to long-term relational and emotional instability.

(Schore, 2001)

None of this depends on cognition or language. The trauma is encoded in physiological systems—subcortical networks that operate beneath awareness. These adaptations are real, measurable, and often lifelong unless addressed directly.

IV. Evolution Came First: The Preverbal Nature of Survival

The mismatch between narrative therapy and trauma isn’t just developmental—it’s evolutionary.

Our core survival systems evolved long before language existed. The amygdala, autonomic nervous system, and freeze/fight/flight circuits are millions of years older than storytelling. These systems were designed to detect threat and respond in milliseconds—not to make meaning, reflect, or reframe.

A gazelle doesn’t need to “process” its fear to escape a lion—it just runs.

A human startle response to a car backfiring isn’t about narrative—it’s an ancient danger-detection circuit misfiring in a modern context.

PTSD flashbacks aren’t “interpretations”—they are activations of a pre-linguistic alarm system.

This evolutionary lens adds a third layer to the trauma timeline:

Evolutionary timescale: Basic survival circuits (amygdala, brainstem)

Individual development: Early relational imprints (ANS, attachment, limbic system)

Narrative processing: Language, reflection, meaning-making (late childhood onward)

Talk therapy targets the most recent and fragile layer of the human mind—our verbal, symbolic cognition. But trauma lives primarily in the oldest and most durable systems.

Trying to heal deep survival responses with language alone is like trying to reason with a smoke detector while it’s going off. It’s not “telling a story” about fire—it’s detecting what it was built to detect.

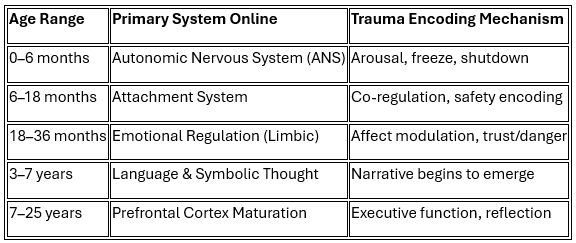

V. The Developmental Timeline of Trauma Imprinting

To understand why talk therapy often fails for early trauma, we need to map when trauma hits which system.

Trauma can occur at every stage, but narrative processing doesn’t become available until years after most regulatory systems are formed. This means early trauma is often pre-verbal and must be approached through the body, not the story.

VI. The Limits of Talk Therapy

Talk therapy has value. For many people, a safe therapeutic relationship, emotional validation, and reflective insight are essential parts of recovery. But for survivors of early or complex trauma, verbal processing alone is often insufficient—and at times reactivating.

Why? Because trauma isn't stored like a movie we can narrate. It's stored as implicit memory: in patterns of muscle tension, autonomic arousal, and procedural learning.

(van der Kolk, 1994)

These are reflexive, body-based responses shaped through experience, not reflection. They can’t be “reframed” because they weren’t framed to begin with.

Consider a trauma survivor who startles at loud noises. No amount of insight will eliminate that reflex. Their nervous system encoded the association between noise and danger before conscious thought was involved. You can’t talk your way out of a flinch.

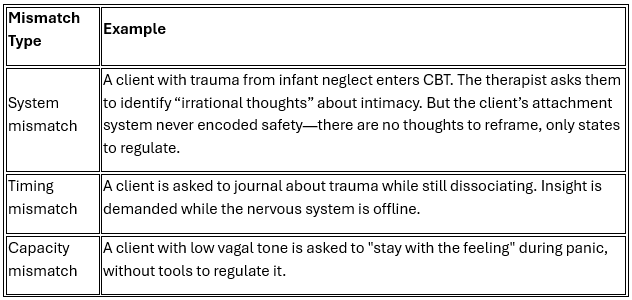

VII. Therapeutic Mismatch: Why Some Therapies Fail

When therapy doesn’t help—or even makes things worse—it’s often because of a mismatch between what the person needs and what the method delivers.

These are not signs of resistance. They are signs that the therapy is hitting the wrong level of the nervous system.

VIII. When Insight Becomes a Burden: The Shame of “Not Getting Better”

There’s a hidden cost to narrative-first approaches that’s rarely named: when talk therapy doesn’t work, the burden often falls on the client.

If the therapeutic frame suggests that healing comes through insight, reframing, or finding the “right story,” then failure to improve feels personal. Survivors may internalize the idea that they’re doing therapy wrong. That they’re not trying hard enough. That they should be able to talk their way out of what their body keeps reliving.

This becomes especially cruel for those with early or developmental trauma, whose dysregulation isn’t a cognitive block—it’s a nervous system adaptation. Their body is doing exactly what it learned to do: protect itself. The problem isn’t resistance—it’s physiology.

When trauma survivors are told to “process” something their nervous system is still bracing against, therapy itself can retraumatize. And when it fails, they don’t blame the method. They blame themselves.

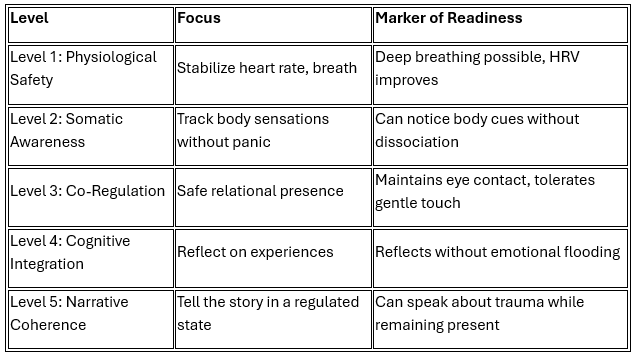

IX. The Regulation Hierarchy: What Must Come First

True trauma recovery must follow a biologically coherent sequence. What matters most is not the content of the story, but the order of operations.

Storytelling should come last, not first. The nervous system must first regain the ability to hold the story without collapse or overwhelm.

X. Predictive Power: Matching Intervention to Trauma Timing

When you combine the developmental timeline with nervous system state and therapy type, you can begin to predict what works and when.

Example Scenarios:

Trauma at 8 months (attachment system) + current hyperarousal

→ Begin at Level 1 (breath, body, co-regulation)

→ Estimated: 6–12 months before narrative processing becomes viableTrauma at age 4 (early symbolic language present) + emotional flooding

→ Begin at Level 2–3 (somatic tracking, relational safety)

→ Narrative integration possible once affect regulation stabilizes

XI. Cross-Referencing the Frameworks: A Unified Model

The developmental timeline, mismatch framework, and regulation hierarchy work together as a clinical guide.

For example:

A client with trauma at 6–18 months is asked to process trauma using narrative exposure (Level 5).

Their current state is dissociation and shutdown.

This creates both a system mismatch (language tool for attachment wound) and a timing mismatch (dysregulation during exposure).

They should instead begin at Level 1–2 and work up.

This logic allows therapists to diagnose mismatch, correct pacing, and predict breakdowns before they happen.

XII. Toward Embodied Models of Healing

Somatic therapies—including Somatic Experiencing, EMDR, Sensorimotor Psychotherapy, and breath- or movement-based interventions—begin with the body. They focus on:

Noticing internal states (e.g., tightness, breath, impulse)

Building tolerance for discomfort

Supporting co-regulation and self-regulation

Re-establishing a felt sense of safety

(Ogden et al., 2006; Shapiro, 2018)

These methods don't exclude storytelling—but they don’t assume it's primary. In fact, narrative work often becomes more effective after the nervous system is stable enough to engage in reflection.

XIII. Conclusion: You Had a Body Before You Had a Story

The body remembers what the mind never knew how to say. Before words, there were sensations. Before interpretation, there was experience. Before narrative, there were nervous systems adapting to survive.

If trauma can occur before thought—as it clearly does—then healing must reach deeper than language. It must begin with regulation, safety, and embodied awareness.

The goal isn’t to reject narrative. It’s to stop treating it as the only path to healing. A regulated nervous system is not the result of a better story—it’s the condition that makes real storytelling possible.

Start with the body. The stories can come later.

If this piece resonated, consider sharing it with someone who’s struggled to “think their way out” of trauma.

I write to make sense of the deeper forces shaping our nervous systems, our politics, and our healing.

You can subscribe for future essays on trauma, systems, and human behavior—grounded in science, not slogans.